Discover Rome and Italy with the best tours

Discover all tours

Vatican

Marvel at the Vatican’s treasure

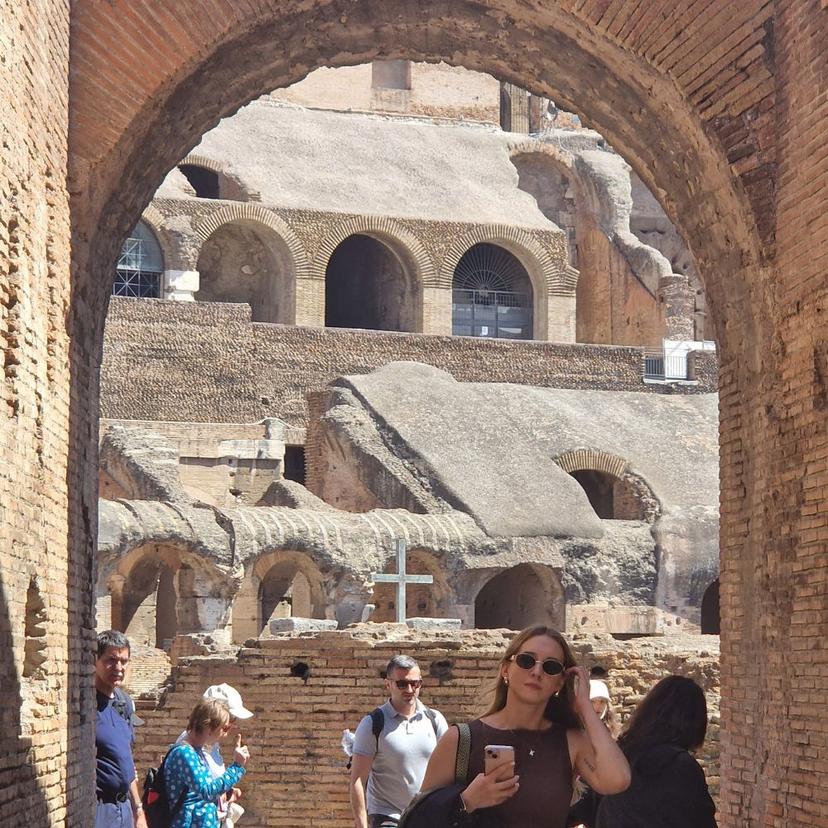

Colosseum

Walks in the footsteps of Emperors and gladiators

Exciting, engaging and educational experiences

Private and small-group tours in Rome and Italy

In the Footsteps of Caravaggio | Private

From € 612,00 for two people

Golf Cart Tour of Rome | Private

From € 660,00 for two people

La Dolce Vita Stroll | Private

From € 425,00 for two people

Doria Pamphilj Gallery Tour | Private

From € 450,00 for two people

Trastevere Food Stroll | Small Group

From € 119,00

Appian Way Bike Tour with Picnic | Private

From € 811,00 for two people

Early Morning Vatican, Sistine Chapel & St. Peter's Basilica - First Entrance | Private

From € 654,00 for two people

Treasure Hunt at the Vatican for Kids & Family | Private Tour

From € 544,00 for two people

Vatican Tour for Kids and Castel Sant’Angelo | Private

Price on request

Vatican Tour by Night | Private

From € 516,00 for two people

Early Morning Vatican & Sistine Chapel Tour with St.Peter's Basilica Access | Small Group

From € 175,00

Divine Day at the Pope's Summer Residence | Private

From € 1880,00 for two people

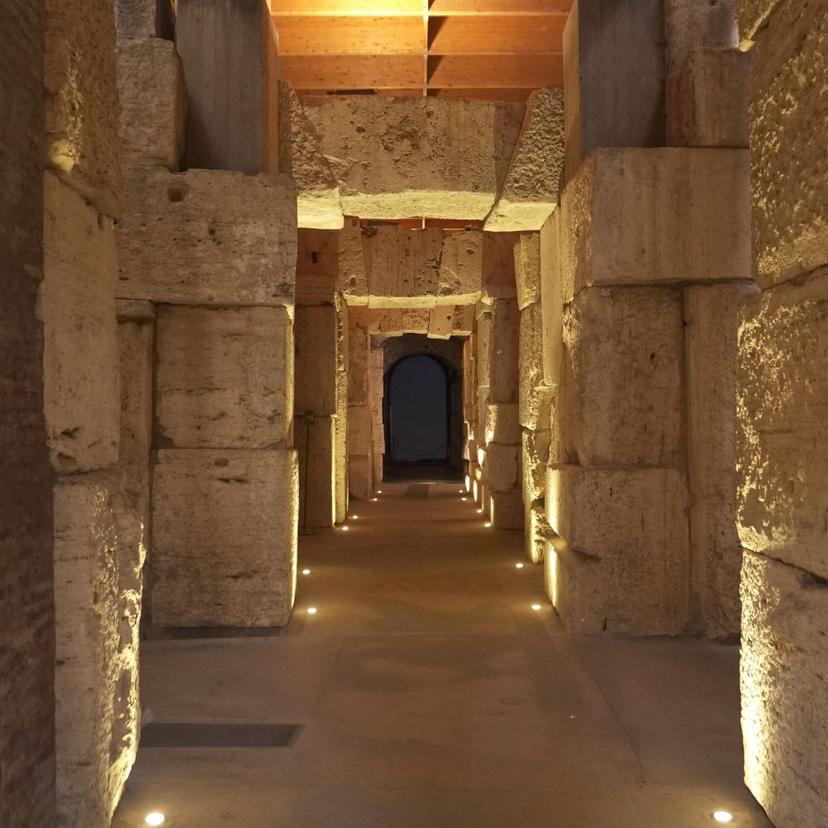

VIP Colosseum Underground & Ancient Rome Tour | Private

From € 705,00 for two people

Colosseum & Ancient Rome | Private

From € 467,00 for two people

Ancient Rome for Kids and Family: Emperors and Gladiators Tour | Private

From € 508,00 for two people

Colosseum & Ancient Rome Tour with Gladiator’s Gate | Small Group

From € 139,00

Express Arena Floor Colosseum Tour | Private

From € 458,00 for two people

Gelato & Italian Biscotti Masterclass | Private

From € 400,00 for two people

Hands-on Pasta Making & Tiramisù Class | Private

From € 590,00 for two people

Pizza Making and Gelato Class | Private

From € 590,00 for two people

Farmers’ Market Shopping with Roman Full Course Class | Shared

From € 165,00

Divine Day at the Pope's Summer Residence | Private

From € 1880,00 for two people

Treasure Hunt at the Vatican for Kids & Family | Private Tour

From € 544,00 for two people

Vatican Tour for Kids and Castel Sant’Angelo | Private

Price on request

Gladiator School for Kids & Family | Private

From € 855,00 for two people

Mosaic and Art Class for Family | Private

From € 410,00 for two people

Raiders of Rome: A Treasure Hunt in the Eternal City for Kids & Family | Private

From € 530,00 for two people

Orientation Tour of Florence with Uffizi Gallery | Private

From € 625,00 for two people

Orientation Tour of Florence with Accademia Gallery | Private

From € 587,00 for two people

Hidden Venice | Private

Price on request

The Jewels of Venice | Private

Price on request

Venice Grand Canal Boat Tour | Private

Price on request

Authentic Gondola Ride | Private

Price on request

Amalfi Coast Day Experience | Private

Price on request

Pompeii & Herculaneum | Private

Price on request

Path of the Gods | Private

Price on request

Pompeii and Mount Vesuvius w/lunch and wine tasting | Private

Price on request

The Golden & Dying Cities: Orvieto and Civita di Bagnoregio | Private

Price on request

Assisi and the Gentle Hills of Umbria | Private

From € 1565,00 for two people

Tarquinia tour | Private

Price on request

Full day in Pienza and Montepulciano | Private

From € 1950,00 for two people

Amalfi Coast with private driver | Private

Price on request

Beyond the crowds lies a city painted in genius. Walk in the footsteps of the great masters and uncover Rome’s most extraordinary artistic treasures with our specialist guides.

Our Tours in Rome

Reviews

Recommended By

Why Choose Us?

Personalized Tours

Discover Italy your own way through customized tours led by our exceptional Italian guides.

Family-Friendly

Spark your kids' imagination and take them on incredible journeys of discovery with our family-friendly tours.

Licensed Guides

Skip the line with our officially licensed Vatican tour guides and gain priority entry to the Holy See.

Culinary Immersion

Experience authentic Italian flavors on our food-and-wine tours and indulge yourself in real Italian style.

From our blog

Show all posts

Best Neighborhoods to Stay in Rome: A Local Guide for Travelers

Roman History Timeline

What Makes the Colosseum Underground Unforgettable

Rome Walking Tours: Explore the Eternal City on Foot with Expert Local Guides

Rome in Spring Travel Guide

Best Museums in Rome

Rome Travel Tips for First Time Visitors

How We Plan a Vatican Visit for First-Timers

Family Owned, Personalized Tours

For more than 20 years, we have been offering both first-time visitors and seasoned explorers unforgettable experiences. Providing everything from full-day city tours to small-group and family-friendly itineraries and helping you unlock Italy’s rich history and culture with our expert, licensed, and native guides. We specialize in private and small group tours of no more than 8 participants, giving you a much more personalized experience at just the right pace. And with priority entrance to Rome’s most famous destinations—including the majestic Colosseum and resplendent Vatican City-you’ll have more time to nourish yourself with knowledge and lose yourself in wonder.