An Introduction

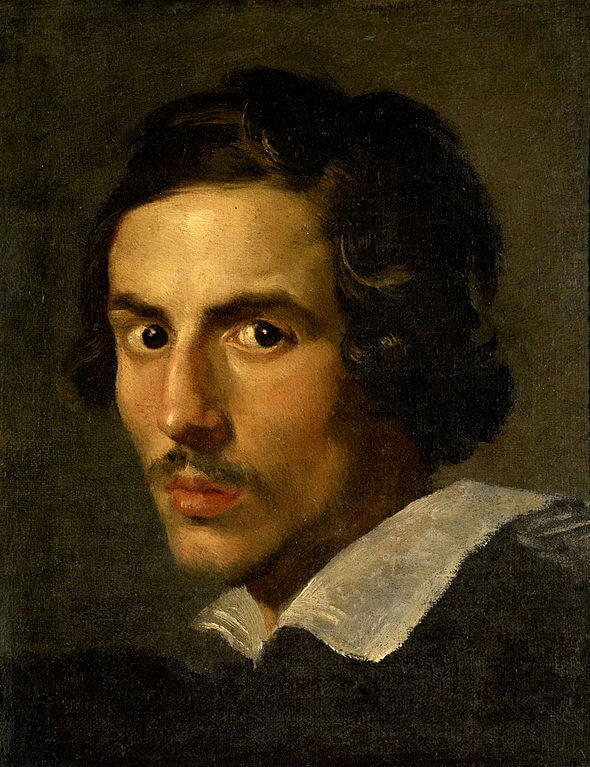

If you have never been to Rome before, you might not have heard of Gian Lorenzo Bernini. But his name is one of the most famous throughout the course of Roman history, deserving mention alongside those of Caesar, Mark Anthony, Michelangelo, and Raphael.

Many scholars believe Bernini to be the last great Italian Renaissance sculptor even though his art is quintessential Baroque (i.e. the movement after the Renaissance). As Michelangelo had helped reshape Florence and Rome a century earlier, Bernini helped monumentalise vast swathes of the Eternal City. Much of Rome’s Baroque grandeur – its churches, fountains, piazzas, and monuments – can be credited to Bernini and his followers.

His work not only brought the stone to life, but brought great heights of emotion. Passion, rage, fear, love, and ecstasy infuse each one of Bernini’s many masterpieces. His talent for capturing tension and drama in stone manifests itself across many Galleries and Museums in Rome.

Bernini’s Life

Much of what we see today in Rome was made by Bernini himself. In fact the Baroque style Bernini perfected is ubiquitous throughout the city. Not all of Rome was planned and built by Rome’s emperors. Much of it was planned and paid for by the Vatican in the 17th century.

From the Vatican and St. Peter’s Square to the angel statues bridging Castel Sant’Angelo, to the best piazzas, to the grandest fountains, to the most enlightening churches, to the museums around the world

filled with his work, Bernini’s art surrounds us and he has set the stage for much of the magical transcendence we experience today in Rome.

How can one best summarize and explain Bernini’s life and exceptionalism? What makes his art great? And how can we account for his success?

Not only was Bernini a genius sculptor; he was organised, tireless and blessed with long life.

Bernini had both many talented apprentices and strong patrons who sponsored him throughout the decades. But visitors often marvelled at Bernini. He was simultaneously able to spend long hours sculpting great works and listen to questions and solve problems, while making decisions and managing all aspects of his business. All without skipping a beat.

Taught how to sculpt by his father at a very young age, legend has it, as told by Bernini himself, that the Pope predicted he would become the next Michelangelo. In adulthood, as perhaps the Vatican’s favourite artist (after Michelangelo and Raphael), he had both the advantage of their patronage and the jealousy of his competitors.

But one of the most famous stories about Bernini comes out of this period where he fell out of favour with the Pope, became the underdog excluded from competition. The project was to design a new fountain for Piazza Navona.

Bernini, uninvited, was undeterred and emblematic of his skill and confidence, Bernini composed a model for It anyway. Pope Innocent X was brought into a room that contained the model and he was smitten. Begrudgingly, the Pope relented and said of Bernini, “The only way to resist executing his works is not to see them.”

That model was the Fountain of Four Rivers which stands today and is one of the marvellous aspects of Rome.

But to know Bernini better, there were 3 key relationships in his life that give us a better understanding of who he was and they are Cardinal Borghese, mistress Costanza, and fellow architect Francesco Borromini.

Cardinal Borghese was Bernini’s most ardent supporter and patron whose family was not only one of the most powerful in Italy, but whose uncle was the pope for a time. Scipione Borghese’s primary endeavour in life, other than running the Vatican, was in collecting fine art. Using much of his family’s wealth he not only accumulated many great works, but also dedicated his palace and home as a venue to showcase these great works. Many great works are preserved today because of his family’s collection. Today, that home, the Borghese Palace, is a museum open to the public and an elegant gallery of some of Rome’s best art.

For this favoured and genius son of Rome with such long life, there was sure to be some calamity. Bernini had an affair with Costanza, who was the wife of one of his assistants. Bernini’s sculpture of her likeness is one of his greatest works in a rare depiction of women of the day. When Bernini then suspected Costanza of involvement with his brother, he badly beat him and ordered a servant to slash her face with a razor. Costanza was sent to prison on charges of adultery and fornication. Luigi was exiled to Bologna for his own safety. Bernini was penalised, but his patron and friend Urban VIII waived the fine on the understanding that now the Cavaliere would get married. Bernini did so and sought redemption for the remaining days of his life by attending mass daily thereafter. Costanza became terribly ill in prison, but after her release she began a business and became a notable art dealer in Rome.

Bernini was fiercely competitive and so were his fellow artists, but none perhaps more so than Francesco Borromini, an architect in Rome. They often competed for commissions and were critical of each other’s art. Publicly displaying their contempt for each other with artistic insults chiselled on the walls of Rome, their feud was well known. But perhaps most embarrassing to Bernini was a reprimand from the Pope and the Vatican’s commission established to investigate the basilica’s unsound twin bell towers that Bernini constructed. They evidently were unsound structurally due to the soft soil below and threatened to collapse the entire façade.

A sculptor first and foremost, Bernini, was in fact also an accomplished architect. As brilliant as Bernini was, Borromini, a dedicated architect, did not miss the chance to criticize Bernini’s. In the end, Bernini fell out of favour with the Vatican, took it very poorly, and deteriorated in health. To Bernini’s credit though, although the foundation of those twin towers was flawed, his design inspired followers and we see their imitations of his vision today in Piazza Navona and elsewhere. A new, frugal pope opened a window of opportunity in this low in his career and for what was to come, one of his best works ever: The Ecstasy of St. Teresa and her new chapel, the Cornaro Chapel within the Church of Santa Maria della Vittoria near Piazza della Repubblica. As Simon Shama of the Guardian has written in his article “When Stone Came to Life”:

Everything that Bernini has in his repertoire is summoned to create what Baldinucci calls a “bel composto” – a beautiful, perfectly integrated fusion of all the arts: colour, motion, light, even a sense of the heavenly choir pouring music down on the scene.

And the talent for which he has been most criticised, the one that has brought about his disgrace – architecture – becomes, in the Cornaro Chapel, a vindication thrown back in the teeth of his critics.

Bernini and the French Period

At the end of April 1665, and still considered the most important artist in Rome, if indeed not in all of Europe, Bernini was forced by political pressure (from both the French court and Pope Alexander VII) to travel to Paris to work for King Louis XIV, who required an architect to complete work on the royal palace of the Louvre. Bernini would remain in Paris until mid-October. Louis XIV assigned a member of his court to serve as Bernini’s translator, tourist guide, and overall companion, Paul Fréart de Chantelou, who kept a Journal of Bernini’s visit that records much of Bernini’s behaviour and utterances in Paris.

Bernini’s popularity was such that on his walks in Paris the streets were lined with admiring crowds. But things soon turned sour. Bernini presented some designs for the east front (i.e., the all-important principal facade of the entire palace) of the Louvre, which was, after a short while, rejected. It is often stated in the scholarship on Bernini that his Louvre designs were turned down because Louis and his financial advisor Jean-Baptiste Colbert considered them too Italianate or too Baroque in style. In fact, as Franco Mormando points out, “aesthetics are never mentioned in any of [the] . . . surviving memos” by Colbert or any of the artistic advisors at the French court. The explicit reasons for the rejections were utilitarian, namely, on the level of physical security and comfort (e.g., the location of the latrines).

Other projects suffered a similar fate. With the exception of Chantelou, Bernini failed to forge significant friendships at the French court. His frequent negative comments on various aspects of French culture, especially its art and architecture, did not go down well, particularly in juxtaposition to his praise for the art and architecture of Italy (especially Rome); he said that a painting by Guido Reni was worth more than all of Paris. The sole work remaining from his time in Paris is the Bust of Louis XIV. Back in Rome, Bernini created a monumental equestrian statue of Louis XIV; when it finally reached Paris (in 1685, five years after the artist’s death), the French king found it extremely repugnant and wanted it destroyed; it was instead re-carved into a representation of the ancient Roman hero Marcus Curtius.

Now you just have to admire Bernini’s Masterpieces with your own eyes! Enjoy our special tours:

Borghese Gallery Private Guided Tour