Since its fabled foundation by Romulus in the 8th century BC, the Eternal City has been eternally divided, cleaved in half by the River Tiber which winds directly through its center.

On its west bank you’ll find tranquil Trastevere, the scenic Janiculum Hill and, of course, the Vatican City and Saint Peter’s Basilica. On the east are most of our traces of ancient Rome. For it’s here that we find the many temples and theaters – as well as such attractions as the Colosseum and Roman Forum – that once made up the heart of the ancient capital.

Connecting the two are a number of beautiful bridges – structures bridging the gap between the ancient, medieval, and modern centers of the city. Walks Inside Rome has published this post to tell you all you need to know about these often overlooked monuments.

Sant’Angelo Bridge

Sant’Angelo Bridge was initially known as the Pons Aelius, after the second name (nomen) of the emperor who built it – Publius Aelius Traianus Hadrianus Augustus (or ‘Hadrian’ for short).

It dates to 134 AD, a period of peace and prosperity in the Roman Empire. Hadrian constructed the bridge to connect the east side of the city with his dynastic mausoleum he was having built on the other side which is now known as Castel Sant’Angelo.

Castel Sant’Angelo and the bridge that runs beneath it weren’t the only monumental legacies Hadrian left in Rome. His most famous monument is surely the Pantheon, which he and his predecessor Trajan largely reconstructed from the Augustan original. Yet it’s in Tivoli, not Rome, where you find the cream of Hadrian’s architectural legacy, namely at the Villa Adriana or Villa of Hadrian.

Since the Renaissance, the Pons Aelius has gone by a different name – Ponte Sant’Angelo, or ‘Sant’Angelo Bridge.’ This is because of the 10 angelic sculptures that line it, two of which are copies of works by Bernini (you can find the others in the basilica of Sant’Andrea delle Fratte nearby). It served as the main thoroughfare along which pilgrims would make their way across the river to the Vatican.

Sant’Angelo Bridge is one of only two bridges in Rome that have retained their original structure (the other being Fabricius Bridge). Of its five arches, three are Roman originals.

Here are our tours that pass by Sant’Angelo Bridge:

Fabricius Bridge

Connecting the east side of the city to Tiber Island since 62 BC, the Pons Fabricius (Fabricius Bridge) is the oldest bridge in Rome to survive to the present day.

The bridge, which dates to 62 BC, around the time of Julius Caesar, was named after the curator viarum – curator of roadways – for the year: Lucius Fabricius. Because it has been situated right next to the Jewish Ghetto since the ghetto’s establishment in the Middle Ages, the bridge was long known as the Pons Iudaeorum (Jewish Bridge).

Only two elements of the bridge can be described as ‘recent’. The first, which date to the 14th century, are the two statues of the double-faced god Janus that greet you on either end of the bridge. The second, rather more modern aspect of Fabricius Bridge is its brick facing.

Everything else – its core peperino ash and tufa structure and arches – is original.

Today, Fabricius Bridge is a tourist attraction in its own right. Many visitors to Rome cross it to explore Tiber Island before walking over to Trastevere or the Jewish Ghetto.

Here are the tours on which we visit Fabricius Bridge:

Vittorio Emanuele II Bridge

Ponte Vittorio Emanuele II is one of the newest bridges in Rome. Designed in 1886, it was inaugurated in 1911, just a few years before the outbreak of World War I.

It spans the River Tiber to connect the Vatican City with the Corso Vittorio Emanuele, which leads to Piazza Venezia and the Capitoline Hill. At either end of the bridge are statues of the winged goddess Victory. Beneath are the scant remains of the Pons Neronianus, a bridge built by the tyrannical emperor Nero.

Ponte Milvio

You’d be forgiven for thinking that Ponte Milvio was a bridge too far. Quite some way to the north of Rome’s historic center, it marked the northernmost boundary of the ancient city limits. But of all Rome’s bridges, the Milvian Bridge has the most fascinating story to tell.

It was here on the morning of October 28, 312 AD, that two rival Roman emperors drew up their armies in a contest for the imperial throne. The first was Maxentius, an imperial pretender, whose villa still lies off the Appian Way and basilica still looms over the Roman Forum. The second was Constantine, the imperial claimant, who was returning from campaign to secure what he considered his imperial birthright.

Constantine oozed confidence. The night before the battle, he had seen a sign in the sky – a cross under which the words in hoc signum vincis (‘under this sign you will win) were written. Later that night he dreamt that Christ himself had visited him, assuring him of his imminent victory if he would but command his men to pain crosses on their shields.

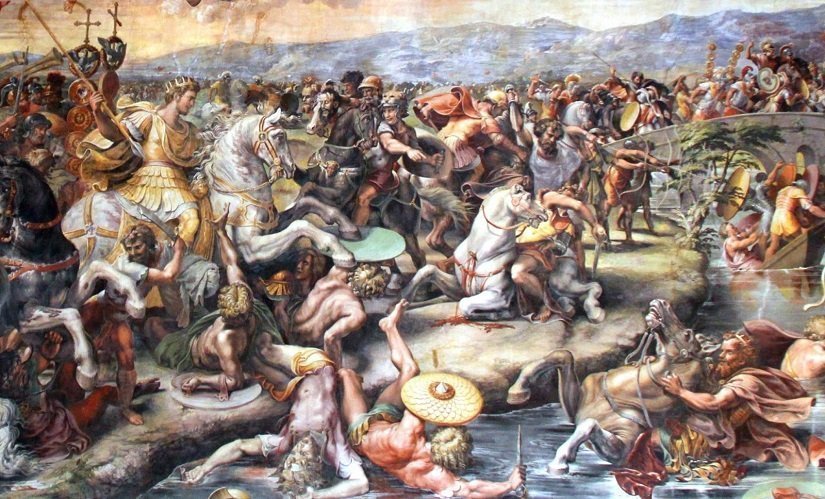

The aspiring emperor Constantine followed this advice, and got his due rewards. His army won a crushing battle at Milvian Bridge, as is depicted on this fresco which decorates the walls of the Vatican’s Raphael Rooms. Constantine’s army drove Maxentius and his men back towards Rome across a hastily-constructed wooden pontoon. It gave out under the weight, throwing Maxentius and his men into the River Tiber. Under the weight of their armor, they drowned.

Few people know this bloody episode in the history of the Milvian Bridge. Instead, what draws most tourists today is its reputation as the ‘Padlock Bridge’ of Rome, so-called on account of the locks left on its railings by young enamored couples.

But the city authorities are clamping down, both figuratively and literally, on these locks, removing them with bolt-cutters in an attempt to clamp down on this illicit practice.