Rome’s Jewish Ghetto preserves a fascinating history, spanning antiquity to today through the turbulent Middle Ages. Mingled among its many monuments are an ancient theater, imperial portico, and the largest synagogue in the city, not to mention other nameless delipidated buildings dating back centuries.

Now an affluent, vibrant, and picturesque part of the historic center, the Jewish Ghetto of Rome masks an unsettling history. For this was once Rome’s poorest neighborhood – home to its most persecuted citizens, whose adherence to their faith earned them the ire of Pope Paul IV.

Read on to discover the history, attractions, and fascinating stories of the Jewish Ghetto of Rome.

History

Rome's first Jewish settlers

Rome’s first Jews arrived in the 2nd century BC, brought over as slaves from the Eastern Mediterranean. Establishing their roots in the city, they lived alongside their pagan neighbors, never particularly comfortably because of differences in worship and customs, but, for the most part, not openly hostile either.

One thing that separated Rome's pagan and Jewish citizens was their respective burial traditions. While cremation was common practice among Rome's pagans, Jewish law mandated that the dead should be buried.

Hence, along the Appian Way, we have some of the oldest Jewish Catacombs, the Vigna Randanini, which between the 2nd and 5th centuries BC became the eternal resting place of several thousand Jews.

The fall of the Roman Empire brought with it the decline of paganism and the ascendancy of Christianity. For centuries, Rome’s Jewish and Christian communities co-existed just as forefathers had done before.

A mistrust of the Jews’ 'otherness’ bubbled away beneath the surface, however, and with the election of Pope Paul IV in 1555, this mistrust became converted into policy.

The creation of the Jewish Ghetto

On July 22, 1555, Paul IV issued a papal bull (edict) known as the cum nimis absurdum.

Named after its first three words, which refer to the absurdity of the Jews being able to retain their rights and continue living as an independent community, the bull placed restrictions on all aspects of Jewish life. It affected the Roman Jews' religious, legal, economic, and - in terms of where they could live - physical rights, immediately rendering them second-class citizens.

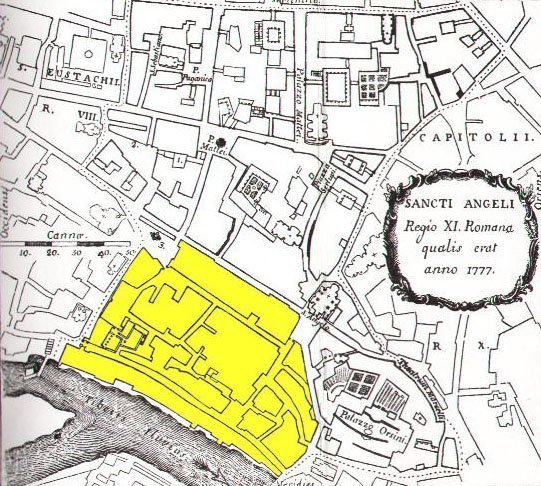

Paul IV’s edict set in motion the establishment of the Jewish Ghetto of Rome: a walled area near the often-flooding Tiber where the city’s 2,000-or-so residents would be forced to reside. Conditions were cramped and living conditions squalid. To rub salt into the wounds of their persecution, the Jews were made to pay for the construction cost of the wall built to contain them.

Because Jews were forbidden from working all but the most basic of jobs, the Ghetto’s inhabitants were incredibly poor. On the rare occasions they were granted permission to leave the Ghetto, men would be made to wear pointed yellow hats and women a yellow veil - the same clothing worn by the city’s prostitutes.

The humiliation didn’t stop there. Every year, the Jews would have to petition for permission to continue living in the Ghetto. What’s more, every year they would have to make the short journey to the Roman Forum to swear an oath of allegiance to the Pope beneath the Arch of Titus - a symbol of their ancient subjugation.

Because the Ghetto was so built up, the area was dark and damp, rarely warmed by the Roman sun. Whenever the Tiber flooded it brought with it the risk of disease, and on many occasions deadly pestilences ravaged the Jewish Ghetto.

In 1656, for example, 800 of the Ghetto’s 4,000 inhabitants succumbed to the plague - their proximity to one another sealing their death warrants.

Only in 1882 did the Italian State formally abolish the Jewish Ghettos across the country and only in 1888 were the walls of the Jewish Ghetto in Rome torn down for good. The watercolor below, painted by Ettore Roesler Franz, dates to around 1880, and shows conditions in the Jewish Ghetto during the death throes of its existence.

Useful Info

OPENING HOURS:

Always Open

What to do in the Jewish Ghetto

- Visit the Great Synagogue

- Explore the ancient sites - the Theater of Marcellus and Portico of Octavia

- Seek out the Fontana delle Tartarughe - the Fountain of the Turtles.

What to eat in the Jewish Ghetto

One of the greatest things to emerge from the hybrid of cultures and inhabitants that have lived in the Jewish Ghetto is the food, known in Italian as la cucina ebraica.

Carciofi alla giudia - fried artichokes - are the most famous, but there’s so much more. A classic is ‘cucina ebraica tripolina’, heavily influenced by the Libyan Jews who fled to Rome in the 1960s.

The flavors are unexpected. There is fish, stewed with paprika and cumin, and a must try is cershi: a delicious squash puree prepared with lots of garlic.

FAQs

When were the ghettos first established?

The first ghetto was not in Rome, but in Venice. Instituted by papal edict on March 29, 1516, the ghetto was established in Venice’s Cannaregio neighborhood, secluded from the other islands by two bridges that were only opened during the day.

What is the Jewish Ghetto in Rome?

The Jewish Ghetto is a small area in Rome, between the River Tiber and the Campus Martius, to which the city's Jewish population were confined during the Middle Ages.

The Jewish Ghetto was in use almost continually from the mid-16th to the late-19th century. Its small size, and the poverty of its residents, made it one of the most challenging places to live in Rome, if not in the whole country: subject to frequent flooding, rife with disease, and overly built-up.

Where does the word ghetto come from?

There are several theories for this. Although none can be conclusively proven, etymologists believe the first is the most likely.

- Ghetto meant street (like the German Gasse, Swedish Gata, and Gothic Gatwo)

- Ghetto derives from the Italian gettare, meaning ‘to throw away.’

- Ghetto derives from the Italian borghetto, meaning ‘little town.’

- Ghetto derives from the Hebrew get: a divorce document.