When it comes to discovering Bernini and understanding what differentiates him from other renaissance and baroque sculptors, it is very easy to see why he was so great. The challenge is that he led such a long life and was so prolific that there are so many works to discover and appreciate.

Overall, Bernini’s works seem more lifelike, are filled with more emotion, and attempt to capture the moment that epitomizes their story.

As Sasha Slater of The Telegraph wrote:

“Where Michelangelo’s David stands daydreaming, Bernini’s is frowning, biting his lower lip, bending sideways and twisting his sling taut to let fly a stone. Pluto, in the act of abducting Persephone, leers as he grabs her plump waist and dimpled thigh, while Cerberus snarls at his feet. Aeneas heaves Anchises on to his shoulders to save him from the sack of Troy and sets off to found Rome.”

The Baroque saw significant changes in the art of sculpture; Bernini was at the forefront of this. The statues of the Renaissance masters had been strictly frontal, dictating the spectator to view it from one side, and one side only.

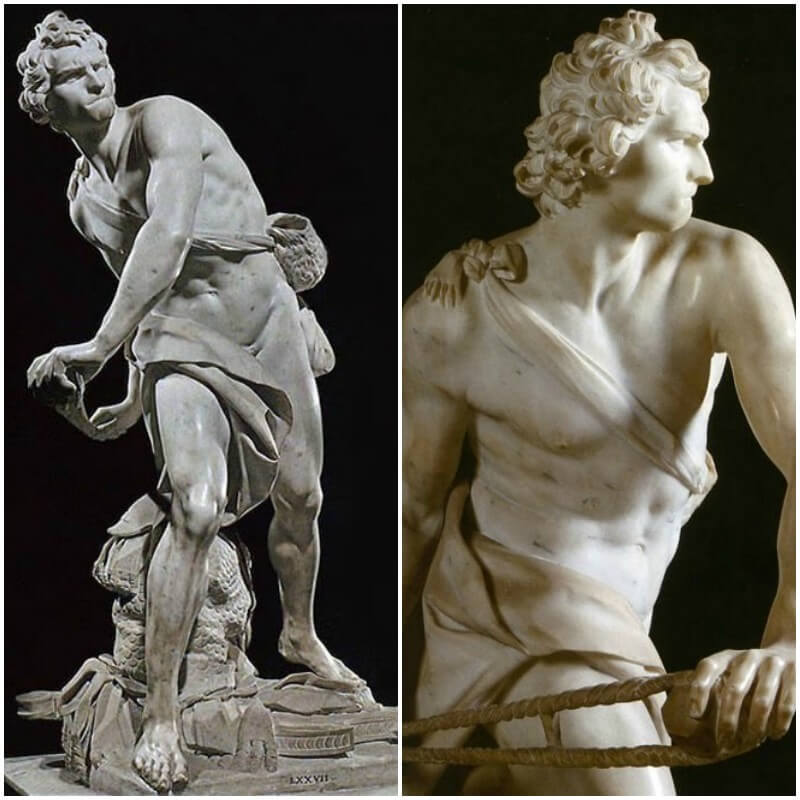

The David: Bernini Vs Michelangelo

Bernini’s David is a 3-dimensional work that needs space around it and challenges the viewer to walk around it, in order to contemplate its changing nature depending on the angle from which it is seen.

The sculpture relates to an unseen entity – in the form of Goliath, the object of David‘s aggression – as well as to the spectator, caught in the middle of the conflict. The warrior even literally oversteps the boundaries between life and art, putting his toes over the edge of the plinth. The conventions of the time, as well as space, were challenged. Instead of the serene constancy of, for example, Michelangelo’s David, Bernini has chosen to capture a fraction of time in the course of a continuous movement. Thus the latent energy that permeates Michelangelo’s David is here in the process of being unleashed.

On an emotional level, Bernini’s sculptures were revolutionary for exploring a variety of extreme mental states, such as the anger seen here. David‘s face, frowning and biting his lower lip, is contorted in concentrated aggression.

Baldinucci tells an anecdote of how Barberini would hold a mirror up to Bernini’s face so the artist could model the sculpture on himself. This bears witness to Bernini’s working methods, as well as to the close relationship he enjoyed with the future pope.

In addition to attempts at realism, David also followed contemporary conventions about how a military figure should be portrayed. As Albrecht Dürer previously had postulated, the vir bellicosus—the “bellicose man”—was best represented with the rather extreme proportions of a 1:10 head-to-body ratio. Furthermore, the warrior has a facies leonina, or the face of a lion, characterized by a receding forehead, protruding eyebrows, and a curved nose (David was after all later to become the “Lion of Judah”).

Wrote Howard Hibbard in his book on Bernini.

“Bernini’s early development is crowned by three great works carved for Cardinal Scipione Borghese: the Pluto and Persephone, the Apollo and Daphne, the David These show successive mastery and more – the brilliant series contains within it no less than an artistic revolution”.

Bernini’s New Style & the Neptune

The new style begins with the Neptune and achieves its first unequivocal impact with the Pluto, which stuns us from the outset by its amazing virtuosity. In this and succeeding works Bernini seems bent on pushing the resources of marble sculpture to their extremity. Bernini’s stupendous technique as a marble cutter seemingly allowed him to model the obdurate material as if it were dough and achieve the effects of bronze, which is cast from clay or wax models. (He has been chastised for just this achievement by artistic moralists whose criteria are based on abstract conceptions such as ‘truth to materials’).

Subtraction vs. Addition

Renaissance writers, basing their theory on antiquity, had contrasted the process of chipping away from a block with that of building up and modelling out of plastic material: subtraction v. addition.

Michelangelo’s disdain for the latter process is well known. Bernini, here, achieves the pictorial effects of clay modelling (addition) through the traditional methods of carving (subtraction); and his startlingly realistic technique is at the service of a momentary vision.”

Pluto & Persephone

The action is depicted at a climactic moment:

Pluto seems to have just snatched the voluptuous maiden, who twists, struggles, and cries aloud in vain. The texture of the skin, the flying ropes of hair, the tears of Persephone, and above all, the yielding flesh of the girl in the clutch of her divine rapist as the triumphant god steps past the border of Hades, symbolized by the frightening form of Cerberus that also serves as a necessary support for the group.

All initiate a new phase in sculptural history.

We can follow the evolution of Bernini’s design from a drawing that seems to show that his first ideas were based on the famous group by Giovanni Bologna. Such statuary remains incomplete from any one point of view: the composition sends the observer around the statue in an unrequited search for completion. This gyration prolongs and delays final comprehension of the group while enriching its meaning through innumerable views. It might be said, in fact, that the sum of these views is the work.

One Point-of-View

Bernini’s new approach strives, above all, for immediate and total impact upon the observer. In order to achieve this, he needed to resolve the action as completely as possible upon one point of view. Profiting from his experience with the Neptune, where a focus for the composition was provided by the relationship of the sea god to the water below, Bernini next created a group with one, and only one, predominant aspect. Thus Bernini’s vision is pictorial rather than conceptual.

The Pluto and Persephone is a kind of sculptured picture, but unlike either painting or relief, the group in the round gains by the spatial immediacy of three full dimensions and by rich secondary views. It must be emphasized that these other views are distinctly subordinate. The group was carved to be seen from the front and like the other Borghese sculptures it stood against a wall. As a gesture of friendly goodwill Cardinal Borghese – temporarily out of favour – gave the newly completed group to Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi, the Pope’s nephew.”

To replace it, Borghese commissioned another group representing Apollo and Daphne (or perhaps the Apollo and Daphne, once begun, seemed so promising that the Cardinal felt he could afford to give the Pluto away).

This group carries the pictorialism of the Pluto & Persephone to heights never attempted before.

The Ovidian subject, Daphne, while common in paintings, was rare in sculpture for reasons that can be readily imagined neither hot pursuit nor transformation from flesh to tree seemed remotely suited to treatment in three frozen dimensions.

Again Bernini chose the crucial moment:

- just as Apollo thinks he has achieved his goal, Daphne‘s fleeing form begins to be enveloped by the encircling bark; her fingers leaf out; her toes take root.

- Apollo has just caught up with his beloved and encircles her waist with a confident arm; but his facial expression indicates the beginning of an awareness that something has gone wrong.

- Daphne seems ignorant of her transformation as she looks back over her shoulder, lips parted in fright.

- Her mouth seems to frame a silent scream as her face goes blank under the force of transformation – a parallel to the paradox of the form, still running, taking root before our eyes.

- Daphne‘s hair swings around as a result of her sudden arrest and blows free with a lightness that Bernini himself felt he never equalled.

The whole statue is one of the most successful illustrations of a literary passage ever made,” as written by Howard Hibbard in his book Bernini.

The statue of Aeneas & Anchises by Bernini has a unique history in that experts were unsure exactly who its sculptor was. The sculpture was, for a long time, considered to be by Bernini’s father, Pietro. Howard Hibbard, an author and expert on Bernini, wrote, “The Aeneas itself is derived from Michelangelo’s Risen Christ in Santa Maria Sopra Minerva. Although this Christ is perhaps the weakest figure Michelangelo ever produced. What positive qualities the Aeneas does have are in part derived from that source:

Muscles, sinews, and veins play realistically under the skin of Aeneas to give his body a virility lacking in the head. The sagging skin of the old man is subtly differentiated from that of the son and recalls Bernini’s study of the antique Seneca; the pudgy Ascanius, who gave Bernini another opportunity for a display of surface texture, completes Bernini’s three ages of Man. The tousled, leonine hair of Aeneas again shows the young sculptor’s study of Hellenistic models – in short, as Wittkower has said, ‘we are witnessing the birth of a realistic style, ushered in by the invigorating study of classical antiquity’.

The statue has a religious importance as well: the aged man carrying the family penates from the fallen city, supported by his son, illustrates piety toward God and toward a parent, and offered an ancient example of the triumph of faith over adversity, a popular theme in Counter-Reformation Rome.

The Aeneas seems to have been a success among the cognoscenti,” wrote Howard Hibbard in his seminal work about Bernini’s life and works.

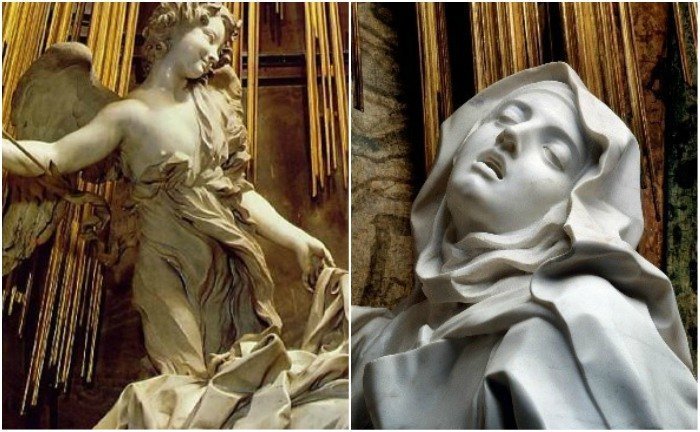

The Ecstasy of St. Theresa

This sculpture is both one of Bernini’s most controversial works and one of his most renowned achievements which he completed for a side chapel in Rome’s Church of Santa Maria della Vittoria from 1645 to 1652. Bernini called it his most beautiful creation.

What Bernini created here, at first sight, seems to be a profane depiction of a saint (and nun) experiencing the power of God — feeling one with the Lord to the point of saintly ecstasy, but it was also a political statement. It was a defense against an infringement on women’s rights that was growing in the world at the time as a more conservative branch of Christianity was rapidly growing in popularity: Protestantism.

Born in central Europe, this new religion had reached the studios, cathedrals, and that open-air canvas they called Rome. Restricted by the Vatican suddenly on what they could paint and how they did so, resulted in tremendous artistic infringement and backlash. So Bernini in protest used the story of a nun already canonized, St. Teresa. As evidence of her divinity, accounts of ecclesiastical experiences from her diary with the father, son and holy spirit, had earned her sainthood.

The back-story of this sculpture is long, but it originates with an event called the Council of Trento (1545 & 1563) whereby the church made an attempt to moralize its institutions and behaviors of its representatives in contrast to the Lutheran Reformation. After the council, even the nudities of the Sistine Chapel were removed and medical literature was discussing the sinfulness of female sexual pleasure towards the goal of reproduction.

It is in this context that Bernini’s genius was able to produce one of the greatest examples of religious art. Using the autobiography of St. Teresa of Avila in which Sister Teresa recalls a vision in which an angel appeared before her and pierced her heart with a golden spear, Bernini integrates a nun-turned-saint’s evidence of divine love with the subversive power of female orgasm. Conceptually, St. Teresa’s bodily arrest is a metaphor for her spiritual euphoria, but his rendition of this concept is so strikingly visual, explicit, and engaging that viewers are stunned at its sight.

I saw in his hands a long golden spear […] This, he plunged several times into my heart, that it penetrated to my entrails. […] The pain was so severe that it made me utter several moans, and yet such pain was so exceedingly sweet that one cannot possibly desire it to cease. (St Teresa of Avila, 1515-1582)

It is this scene on which Bernini’s statue is based. His angel grips his arrow, preparing to strike again, looking down at the swooning Teresa with a sly smile. Teresa lies overwhelmed beneath, her eyes and mouth in ovals of euphoria, her rippled habit mimicking the spasms charging through her body.

ARTWORKS:

Sculptures

- Busts of Scipione Borghese and Costanza

- Apollo & Daphne

- The David

- Aeneas and Anchises

- Pluto & Persephone

- The Ecstasy of St. Teresa

- Blessed Ludovica Albertoni

- Statue of San Longino

- Truth Unveiled by Time

- Bust of Louis XIV

- Bust of Costanza

- Habbakkuk and the Angel

- Sepulchre of Alessandro VII

- Bust of Scipione Borghese

- Nettuno e Tritone

- Anima Dannata

- Capra Amaltea

- A Faun Teased by Children

- San Sebastian

- Bust of Monsignor Pedro de Foix Montoya

- Ermafraodito dormiente

- San Lorenzo sulla graticola

- Angel with the Crown of Thorns

- Bust of Cardinal Richelieu

- Charity with Four Children

- Anima Beata

- Daniel and the Lion

- Bust of Giovanni Vigevano

- Angel with the Superscription

- Medusa

- Bust of Francesco Barberini

- Santa Bibiana

- Equestrian Statue of King Louis XIV

- Bust of Thomas Baker