Rome has no shortage of monuments commemorating military victories. Even the Colosseum, funded from spoils of war looted from Jerusalem, shouted Roman success and supremacy with the scale of the structure and the spectacles it hosted.

From its earliest days, Rome was militaristic to the core, driven to expansion by existential threats posed by her neighbors. First in Italy, and then abroad. Few structures pay stronger testament to Rome’s bellicose nature than its triumphal arches. And that so many triumphal arches have been reinterpreted and replicated across the ages – from the Arc de Triomphe in Paris to the Soldiers and Sailors Arch in New York City – speaks volumes about how this form of cultural expression was not unique to Rome, but repeats itself across humanity.

What did the Roman triumphal arch symbolize?

The reason we call these arches ‘triumphal’ is because the SPQR (Senate the People of Rome) awarded them to victorious generals returning to Rome to celebrate their Triumph.

Part religious, part propagandistic, the Roman triumph was essentially a victory parade in which victorious generals would adorn the costume of a god and parade through the city to the adulation of the crowds.

Spoils of war would be paraded, coins would be thrown to those who had gathered, and the triumphant general, borne in a chariot with a slave behind him whispering a reminder in his ear that he was just a mortal, would make his way up the Capitoline Hill to make dedications at the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus.

The earliest arches we know about (none of which survive) were erected on the Capitoline Hill and in the Roman Forum. They functioned as a kind of monumental messageboard, displaying the militaristic achievements of prestigious Romans past and present and becoming more and more competitive as time when on. Let’s take a look at some of Rome’s most famous surviving arches.

Arch of Constantine

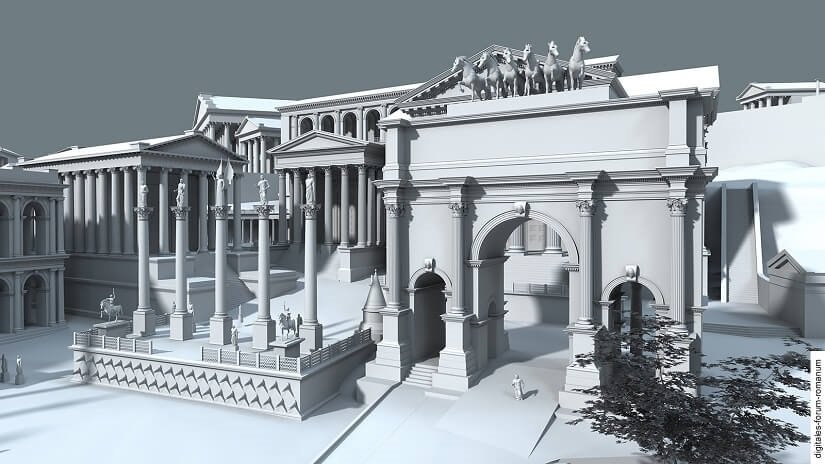

Standing just outside the Colosseum on the ancient route into the Roman Forum, the Arch of Constantine is the largest and most conspicuous surviving triumphal arch in the city. Sharing a similar design to the Arch of Septimius Severus, it stood on the Via Sacra (Sacred Way): the processional route victorious generals took during their parade around the city.

Passing from the Circus Maximus and under the Arch of Constantine, they would then process into the Roman Forum and up the Capitoline Hill to make offerings at the Temple of Jupiter, before dispersing for the day’s banquets, games and other celebratory events.

The Senate dedicated the arch in 315 AD to commemorate Constantine’s victory over his rival Maxentius at the Battle of Milvian Bridge three years earlier. Interestingly, the arch makes no mention of Maxentius, even though it may well originally have been dedicated to him. There are two reasons for this: firstly, it wasn’t a good look for Romans to monumentalise victories over fellow Romans. Secondly, Constantine carried out what we call damnatio memoriae – the damnation of memory – on Maxentius in an attempt to obliterate any trace of his existence. The fact we’re still talking about him today shows he failed in this endeavour.

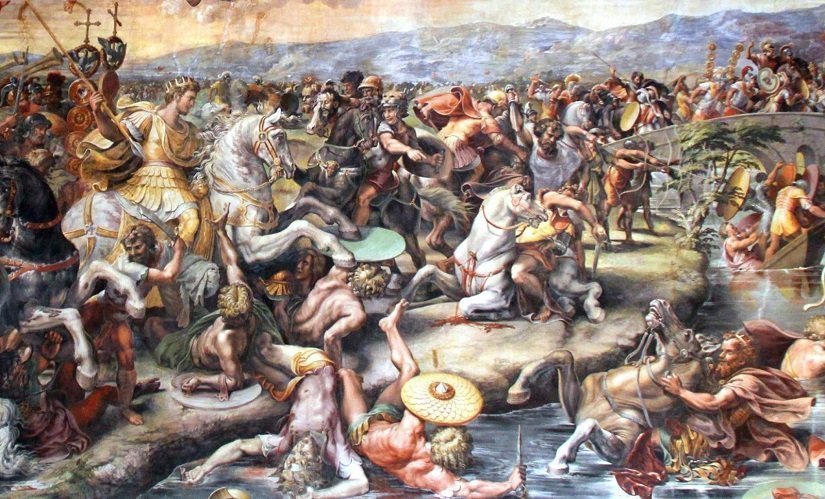

No scenes from the Battle of Milvian Bridge appear on the arch. But if you visit the Vatican’s Raphael Rooms, you can see a much later fresco, executed by Raphael’s students, depicting this significant moment in Roman history. And its significance can’t be overstated – for had Constantine not defeated Maxentius at Milvian Bridge then Christianity may never have taken root to become the dominant religion of the Roman Empire and – consequentially – of today’s world.

Although we call it the Arch of Constantine, the monument could more accurately be described as an imperial collage recyling material from the monuments of several previous emperors including Trajan, Hadrian (who built the Pantheon), and Marcus Aurelius (whose equine statue stands in the center of the Capitoline Museums).

Stripped of the color and statues that once adorned it, the Arch of Constantine is a shell of its former self. Once supported by yellow Corinthian columns of Numidian marble and red, green, and purple porphyry decorating the friezes and statues atop it, in its heyday the Arch of Constantine would have been as eye-catching as the Colosseum itself.

During the Middle Ages, the Arch of Constantine like many other Roman monuments including the Colosseum, was incorporated into fortifications of one of Rome’s foremost aristocratic families. The family in question were the Frangipani, who in the 12th century also fortified the Colosseum and from whom, according to Boccaccio, Dante was descended. By the 15th century, however, they had ceded control of the arch. It was only in the early 2000s that the monument was subjected to the restoration works it needed.

→ Visit the Arch of Constantine, Colosseum, and Roman Forum

Arch of Titus

Standing at the entrance of the Roman Forum, the Arch of Titus was actually erected after the emperor Titus’ untimely death in 81 AD. It was probably dedicated by Titus’ brother and successor, Domitian, whose legacy in Rome includes the circus beneath Piazza Navona, the imperial palace on the Palatine Hill.

We know Titus had died by the time it was dedicated because of the inscription on its front. The giveaway is its reference to the divine – and therefore deceased – Titus, as emperors could only be declared gods after shuffling off their mortal coil.

The reliefs inside the Arch of Titus tell the story of the construction of the Colosseum. Titus was the emperor who finally captured Jerusalem in 70 AD after a protracted war between Rome and Judaea. After storming the city, the Romans sacked it, looting the treasures of its temple and taking them back with them to Rome.

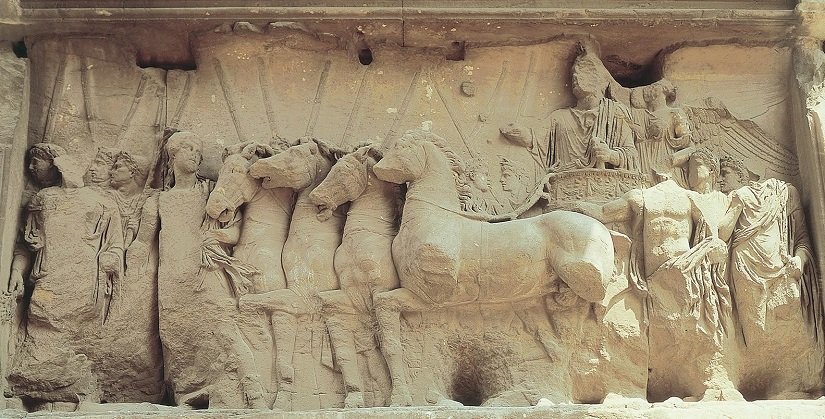

The relief on the right depicts Titus’ triumphal procession in 71 AD. Standing in his chariot with his soldiers in front, he is being crowned by the goddess Victory (winged, to represent her fleeting nature).

The left relief shows the spoils taken from Jerusalem. Among the most recognisable objects are the menorah – the seven-branched candelabrum mentioned in Exodus (27:21) as the centrepiece of Jewish ritual, the Ark (possibly of the covenant), a pair of golden trumpets, and the shew bread table.

The Romans pawned these invaluable treasures to fund the construction of the Colosseum. Indeed, many of the slaves who were put to work on the amphitheater were slaves taken from Israel. Such then is the potency of the Arch of Titus’ narrative and symbolism that, up until the establishment of the modern State of Israel, Jews had always refused to walk through it.

During the Middle Ages, the arch was fortified – again by the Frangipani family – and incorporated into their stronghold. It suffered terrible damage in the process and had to be almost completely restored in the early 19th century.

→ Explore ancient Rome from a Jewish Perspective

Arch of Janus

The two-headed god Janus may have given his name to the Janiculum Hill, atop which his shrine once stood, but you might be surprised to know that he has nothing to do with this arch.

It might be called the Arch of Janus Quadrifrons (Janus of the Four Faces), but this name only came about because of its unusual four-facing structure. Instead, the monument that stands in the eastern corner of the Forum Boarium, Rome’s ancient cattle market, was dedicated to a certain tyrant-vanquishing emperor.

The ancients mention a certain arcus divi constantini (Arch of the Divine Constantine) in this area, and as Constantine famously celebrated his victory over the ‘pretender’ emperor Maxentius at Milvian Bridge in 312 AD, we can reasonably guess that he was the emperor in question, and that this arch was erected either by him or by his son Constantine II.

Like the Arch of Constantine outside the Colosseum, the Arch of Janus was built from spolia (reused material) stripped from other monuments. The Frangipani family converted it into a fortress in the Middle Ages (as they did the Colosseum and the Arch of Constantine) and the arch stayed as such until the 18th century.

In its recent history, the Arch of Janus was engulfed in a bombing carried out by the Sicilian Mafia on July 27 1993. At midnight, the Mafia detonated a car-bomb outside the church of San Velabro in Foro, damaging the arch’s structure and leading the authorities to seal it off to the public. Fortunately – and remarkably – there were no fatalities.

None of the 48 statues that we believe once filled its niches have survived, nor has its ancient attic. Get close enough, however, and you can make out its four keystones which represent Rome’s most worshipped gods and goddesses – Juno, Minerva, Ceres, and Roma herself.

Arch of Drusus

One of the young, up-coming stars of the Augustan Age (31 BC – 14 AD), Drusus was one of the greatest generals of the early Roman Empire. He was the first man to lead the Roman legions across the Rhine into Germany, enjoyed considerable success against several Germanic tribes: defeating, among others, the Sicambri, the Frisii, the Batavi and the Macromanni.

Then, in 9 BC, he fell off his horse and died.

Drusus’ memory lived on literature and artwork, but this arch has nothing to do with him. Archaeologists have dated the so-called ‘Arch of Drusus’ to the early 3rd century AD and assigned it the function of carrying water from one of the Roman aqueducts, the Aqua Antoniana, (a branch of the Aqua Marcia) to the Baths of Caracalla.

Of the arch’s original three passageways, only the central one has survived up to today. If the remaining third is anything to go by, it seems the entire monument was made of travertine and given a marble facing.

→ Pass under the Arch of Drusus

Arch of Septimius Severus

Rising up between the Curia (Senate House) and Rostra at the foot of the Capitoline Hill, the triumphal Arch of Septimius Severus dominates the Roman Forum.

It was dedicated in 203 AD to monumentalize the military success of Rome’s first Severan emperor. As was customary on Roman triumphal arches, it contained a dedicatory inscription listing the emperor’s many titles (Augustus, Pater Patriae, Pontifex Maximus, Proconsul etc.) and explaining why the Senate and People of Rome saw fit to dedicate an arch in his honour (for beating the Parthians, saving the Republic and expanding the Empire in this particular case).

Crediting Septimius Severus with actually saving the Republic is a little disingenuous. In reality, the emperor did little more than survive the political fallout that followed the death of Commodus, and outlast his rivals Pescennius Niger and Clodius Albinus in their own bids for the imperial throne by fighting a civil war.

But credit where credit’s due – he did expand the Empire, pacifying the Parthians and incorporating much of Syria into Roman territory.

The Arch of Septimius Severus displays a pretty comprehensive visual programme. As well as two depictions of Mars the god of war, a representation of Hercules, several natural divinities including the four seasons and the river gods, it contains the more profane illustrations of Roman legionaries leading away Parthian prisoners.

Face the arch from inside the Roman Forum and you’ll see that the illustrations provide a comprehensive narrative of Severus’s campaigns. To get the chronology you have to go from left to right and bottom to top.

Firstly you see the Roman army departing their camp, their battle with the Parthians, the emperor Septimius Severus himself delivering a rousing victory speech. Then comes the liberation of Nisbis, the siege and capture of the city of Edessa, and Severus’s reception amongst its populace as a god.

We then see another submission, this time of King Abgar and the Osroeni, which leads to Severus delivering another speech to the army. The campaign continues, he attacks Seleucia, and drives the Parthians to flight, bringing about Seleucia’s surrender and Parthia’s submission to Roman rule.

Finally, Severus’s army attack Ctesiphon – a city just south of modern-day Baghdad – with a siege tower, and after its capitulation the emperor gives a final speech to his victorious army outside it. Safe to say that it shows a lot. But it’s what the Arch of Septimius Severus doesn’t show that’s most interesting. And what it doesn’t show is the emperor’s son Geta.

Left to share the throne with Severus’s other son, Caracalla, Geta was murdered by his brother in 211, dying in the arms of his devastated mother. Caracalla then carried out the damnatio memoriae (damnation of memory) of his brother, expunging all visual and epigraphic traces of his existence, including on the arch.

The fact that we know about this shows how his efforts were in vain.

→ Explore the Roman Forum and Arch of Septimius Severus