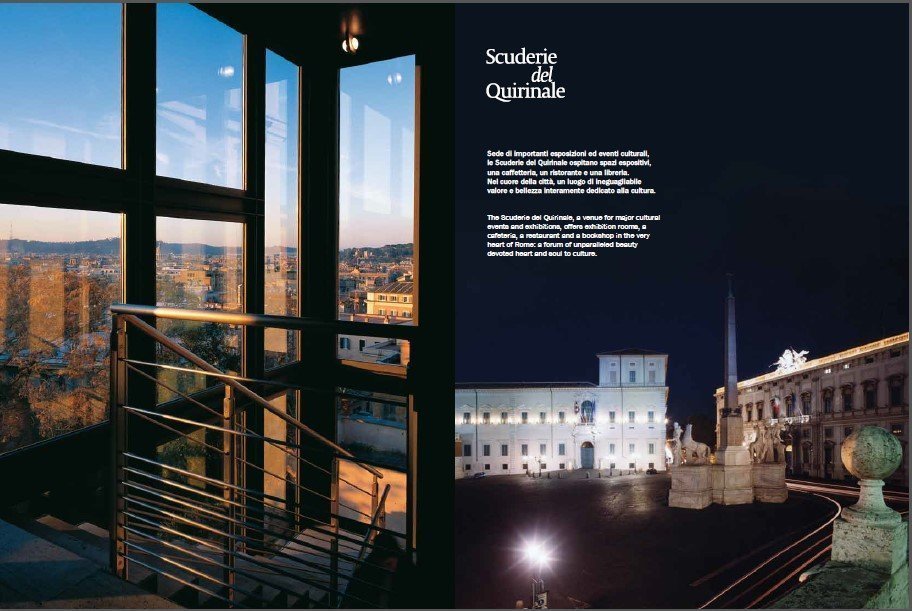

Picasso comes to Rome at the Scuderie del Quirinale

At the Scuderie del Quirinale, a magnificent gallery set atop the highest of Rome’s seven hills beset by Italy’s Presidential Palace and the renowned Colonna Gardens, the former Papal Stables anchored in a great ancient Roman temple, offering both an astounding view of some of the world’s greatest art and the most magical city, will be on display until January 21st 2018 the exhibition titled “Picasso: Between Cubism and Classicism 1915-1925“, a collection of a hundred masterpieces chosen by curator Olivier Berggruen in collaboration with outstanding museums and collections.

The exhibition is supported by 38 lenders. Unique works from Europe, US and Japan. Musée Picasso, Pompidou Center in Paris, Tate of London, MoMA, the Metropolitan Museum, the Guggenheim, the Berggruen Berlin Museum, the Fundació Museu Picasso in Barcelona, and the Thyssen Museum in Madrid are the major lenders.

The exhibition will illustrate the experiments conducted by Picasso with different styles and genres: from the play of decorative surfaces in collages (performed during the First World War) to the stylized realism of the “Diaghilev years”, and from still life to portrait.

From a distance of a hundred years, the exhibition will celebrate Picasso’s 1917 trip to Rome and Naples following Sergei Diaghilev’s company Ballets Russes with poet Jean Cocteau and musician Igor Stravinsky. This was the trip during in which Picasso met and fell in love with Olga Khokhlova, the first dancer in the company and his first wife.

When Picasso arrived in Italy in February of 1917, World War I was raging. Pablo was only 36 years old but was already a great painter. Soon he would be designing ballet sets and costumes and meet Olga.

The exhibition will focus on the method of the pastiche, analyzing the ways and procedures by which Picasso used it as an instrument in the service of modernism, on a journey from realism to the abstraction of the most original and extraordinary of the history of modern art.

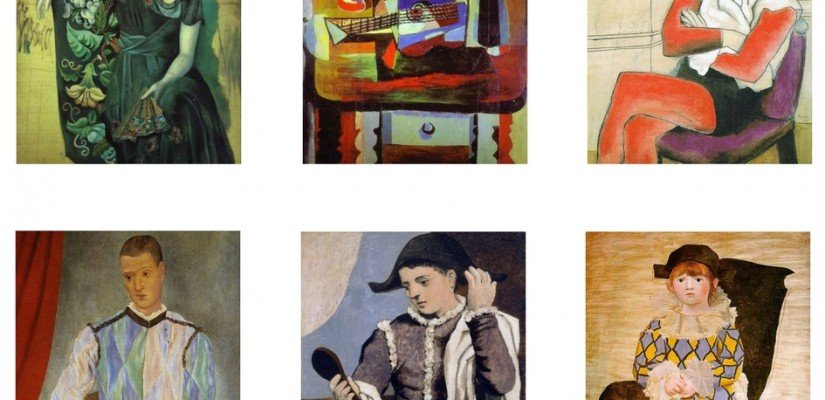

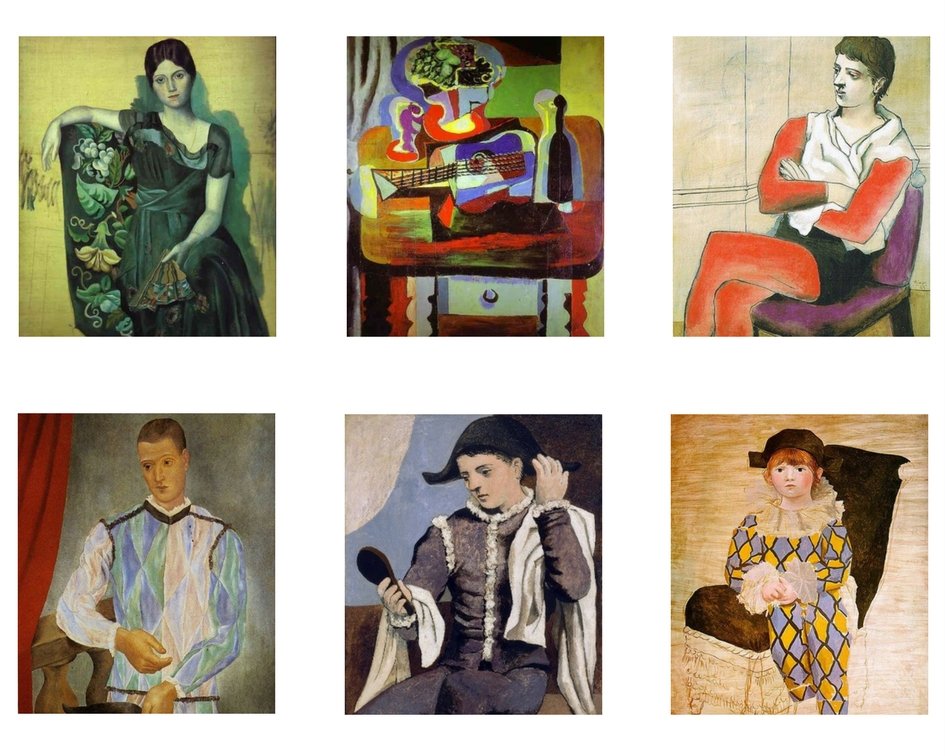

Among them, are the:

- Portrait of Olga in the armchair (1918)

- Arlecchino (Léonide Massine) (1917,

- Still life with guitar, bottle, fruit, plate and glass on table (1919)

- Two women running on the beach (1923),

- Saltimbanco sitting with his arms folded (1923)

- Arlecchino with Mirror (1923)

- Paulo as Arlecchino (1924)

- Paulo as Pierrot (1925)

“It is an exhibition that has been working since 2015 and is one of the most important exhibitions ever dedicated to Picasso in Italy”, said Mario De Simoni, President and Managing Director of Ales spa, co-producer of MondoMostre Skira exhibition and the participation of the National Galleries of Ancient Art.

“Pablo Picasso’s journey to Italy in January of 1917 offered one of the most significant but least investigated influences on his art. It was in Italy where he began his second rose period and absorbed the powerful spirit of Renaissance, Classical, and Mannerist art, as well as Italian culture.”

As writer Jennifer Theriault points out:

It was the Farnese marbles in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale in Naples that would have the most profound effect on Picasso’s art. Over the years the inspiration from these classical Greek and Roman masterpieces burned deep in Picasso’s sculpture. They also propelled him closer toward Neoclassicism in his painting, eventually serving to “classicize his work far more effectively than the antiquities he had studied in the Louvre,” as John Richardson notes in the epic third installment of his seminal Picasso biography “Picasso: The Triumphant Years.”

Back in Rome, Picasso continued meeting artists while making the requisite tourist stops. He got to know members of the Italian Futurist movement, including Giacomo Balla and Fortunato Depero, and visited the Vatican Museums with Enrico Prampolini who commented on the “pleasure with which [Picasso] contemplated the Sistine frescoes and, still more, Raphael’s Stanze and the Vatican museums of sculpture.”

In the book The Italian Journey 1917-1924, editors Jean Claire and Odile Michel explore the fascinating ties between Picasso’s work and his experiences in Italy:

When Picasso went to the Sistine Chapel, for example, he found the Raphaels wanting. “Good, very good,” he remarked, “but it can be done, don’t you think?” Then, turning to the Michelangelo’s Last Judgment: “Now this is more difficult.”