Rome is a city rich in symbolism. From the she-wolf who suckled its twin founders, Romulus and Remus, to the outstretched eagle which symbolizes the vast territorial reaches of the Roman Empire, many Roman symbols have survived the centuries to become part of our collective visual culture. This article takes a look at some of the most well-known symbols of Roman history, sharing some juicy facts about their origin, use, and meaning.

The Symbols of Roman History

The Eagle (Aquila)

Few symbols represent Rome as powerfully as the eagle. Perched atop the legionary standard, its wings outstretched, this ferocious hunting bird represented the span of the Roman Empire.

The Romans originally affixed several symbols to the top of their standards. As well as the eagle, they used the wolf, the horse, the boar, and the human-headed ox. Following Rome’s catastrophic defeat at the Battle of Arausio, however, and Gaius Marius’ radical overhaul of the Roman army in 104 BC, they abandoned these other symbols (signa manipuli, as they were called) leaving only the eagle.

Losing an eagle standard in battle was considered the ultimate humiliation, and the Romans went to considerable lengths to recover them. One such occasion came in 53 BC when Crassus’ Roman army was crushed by the Parthians at the Battle of Carrhae. The Romans suffered a double humiliation – several legionary standards were captured and Crassus, a greedy man by nature, had molten gold poured down his throat.

Augustus eventually retrieved the standards, advertising his achievement on the breastplate of his Prima Porta statue now housed in the Vatican Museums. But while his propaganda portrayed the retrieval of this important symbol of Roman history as a military victory, the reality was that he had to send his best general Tiberius to beg the Parthians for their return.

Nor was this Augustus’ only attempt to recover lost eagle standards. Following Rome’s crushing loss against the Germanic tribes at the Battle of Teutoburg Forest in 9 AD, Augustus and his successors spent decades hunting down then lost standards. The last was only recovered during the reign of Claudius in 41 AD, and was probably placed in the Temple of Mars the Avenger in the Forum of Augustus.

The eagle continued to feature as one of the main symbols of Roman history and emblem of the military even after the arrival of Christianity as the official religion in the 4th century AD. The Arch of Constantine – the emperor who adopted Christianity as the imperial religion – depicts such examples on its south attic (the side you see when facing it from the Colosseum or Colosseum Belvedere).

Likewise, during the 11th century when the imperial capital had long since moved from Rome in the West to Constantinople in the East, the emperor Isaac I Kommenos adopted as his symbol the double-headed eagle: representing the Roman Empire’s dominance over both East and West.

The She-Wolf (Lupa)

Docile in times of peace yet ferocious when provoked, the she-wolf is the quintessential symbol of Rome and her Empire. It relates back to the story of Romulus and Remus, two twins from Alba Longa (modern-day Castel Gandolfo). When their grandfather, King Numitor, was kicked off the throne by his brother Amulius, the usurper ordered for the infant twins to be thrown into the Tiber.

As usual in ancient mythology, the man entrusted with infanticide found he couldn’t go through with it. So instead of drowning them in the river, he abandoned them by the riverbank, to be rescued by the intervention first of the river god Tibernus and then by an unusually maternal she-wolf who just happened to be passing.

Raised in her cave (the Lupercal), the twins were suckled by the she-wolf until a passing shepherd called Faustulus found them and took them home to his wife. They then raised the twins together until they were old enough to return to Alba Longa, reinstate their grandfather to the throne, and fulfil their destiny of founding Rome. Well, for Romulus at least…

The story of the she-wolf was long in circulation before the Romans started writing anything down. We know from the Augustan era historian Livy that from 295 BC a statue similar to the one found in the Capitoline Museums stood at the foot of the Palatine Hill.

Pliny the Elder, an encyclopedist who died in the eruption of Vesuvius that buried Pompeii in 79 AD, also tells us that a statue of the she-wolf suckling Romulus and Remus stood in the Roman Forum. Even in antiquity, the symbol of the city was widespread.

A recent theory, however, suggests that we may have got it wrong.

The Latin word lupa actually carries two meanings. The first meaning of the word is ‘she-wolf’, and refers to the animal itself. The second meaning of lupa is prostitute and refers to the sounds the ancient city’s ladies of the night made to entice their passing customers.

Visit Pompeii and you’ll see the connection. The ancient city’s brothel was called the Lupanar or ‘wolf-den’. In fact, all brothels in ancient Rome went by this Latin name.

So is it possible that when we talk about Romulus and Remus being raised by a lupa, we’ve rather misunderstood the story of their upbringing (or over time have exaggerated the story of their early life being brought up in a brothel instead).

The Fasces

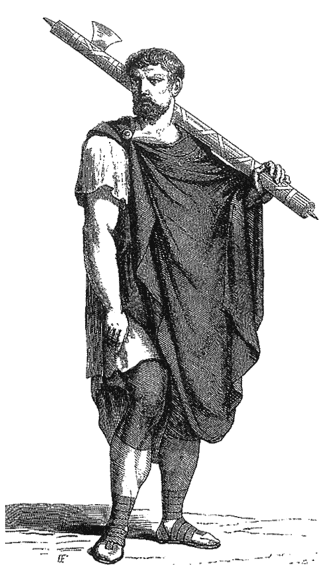

Originating not with the Romans but by the Etruscans, the fasces has become perhaps Rome’s most enduring international symbol. Compared to the eagle or the she-wolf, the symbol itself is visually little-known. Where it survives, however, is in language, where it gives us the root for the word ‘fascism’.

From the Roman Republic, the fasces consisted of a bundle of rods bound together around a single-headed axe. Carried by Roman magistrates in numbers depending on their status, the fasces was a pure symbol of power – of Rome’s dominion over her imperium (empire). The most powerful position possible, that of dictator, entitled the individual to 24 fasces.

When bundled together, these rods symbolised strength (as when bound together they were much harder to break). The axe in the centre on the other hand represented the magistrate’s power – namely his prerogative to administer capital punishment.

Within the sacred boundaries of the city, however, magistrates were forbidden from carrying fasces with protruding blades: the symbolism being that only the peoples’ law-courts were able to administer justice.

During the Roman Triumph – a general’s victory parade around the city into the Roman Forum following the conclusion of a successful campaign – fasces would be wrapped in a laurel wreath. The laurel wreath was a widespread ancient symbol of victory, appearing most famously in ancient Olympia as the award given out to victors.

The fasces has since diffused among western culture to become an emblem of justice, power, and strength, particularly in the United States. The seal of the Senate depicts a crossed fasces at the bottom, the fasces is at the centre of the United States Tax Court and Administrative Office of the State Courts.

But it was because of Mussolini, who drew heavily on the symbol to promote his Fascist revival of ancient Rome, that the fasces is so universally known – not for the power of its image but for the connotations of its name.

The Globe (Globus)

Another Roman symbol that has become part of our daily symbolic life is the globe. Held by the god of gods, Jupiter, as a symbol of his universal dominion, the globe manifests itself on many coins and statues throughout the Roman Empire. Sometimes portrayed under foot or in the emperor’s hand, it symbolised Roman dominion over all the territory they had conquered.

A coin minted under the emperor Hadrian shows the goddess Salus standing on a globe. The message is pretty unambiguous, and Hadrian himself spent most of his reign travelling the length and breadth of his empire while architects back in Italy realised projects like the Pantheon and Villa Adriana.

Constantine went even further in emphasising the extent of the Roman Empire’s dominion. A coin minted during his reign in the early 4th century shows the emperor holding a globe in his hand, attributing the dizzying extent of Rome’s territorial span to himself personally (Constantine never was one for modesty).

The ascendency of Christianity saw modifications to this symbol of Roman history. Most conspicuously was the addition of the crucifix atop the globe, which symbolised the Christian God’s universal dominion. Still a prominent church symbol dating back from the 5th century, the globus cruciger manifests itself all across Christian art.

The most famous example is the Salvator Mundi painting (which in the version attributed to Leonardo Da Vinci controversially portrays the globe without a cross). Yet the globe appears not just in Christian symbolism, but in all contexts relating to power and dominion, not least in portraits of royals ranging from Charlemagne to Elizabeth I to demonstrate the majesty of both their person and of their empire.

Back to top