OPEN: Nov. 1st 2017 – Feb. 20th 2018

The NY Times recently wrote of Bernini, the great Italian Baroque sculptor, and the Borghese Gallery:

“No artist defined 17th-century Rome more than Gianlorenzo Bernini did, working under 9 popes and leaving an indelible mark on the Eternal City. And there is probably no better place to appreciate his talent and genius than the Borghese Gallery in Rome. But during a remarkable exhibition at the Borghese Gallery titled ‘Bernini,’ which runs until Feb. 20th, 2018 visiting may be a once-in-a-lifetime experience.”

Bernini’s Style

As the most representative artist of the Baroque movement, Bernini’s aim was to continue the renaissance tradition of making sculptures that can be viewed from any angle. Bernini took this as an opportunity to display dynamic movement that can capture the narrative in a single frozen moment. For example, Apollo chasing Daphne as she prays to become a tree to escape the enamoured god, her toenails growing into roots and the tips of her upstretched fingers into translucent marble leaves, is the perfect demonstration.

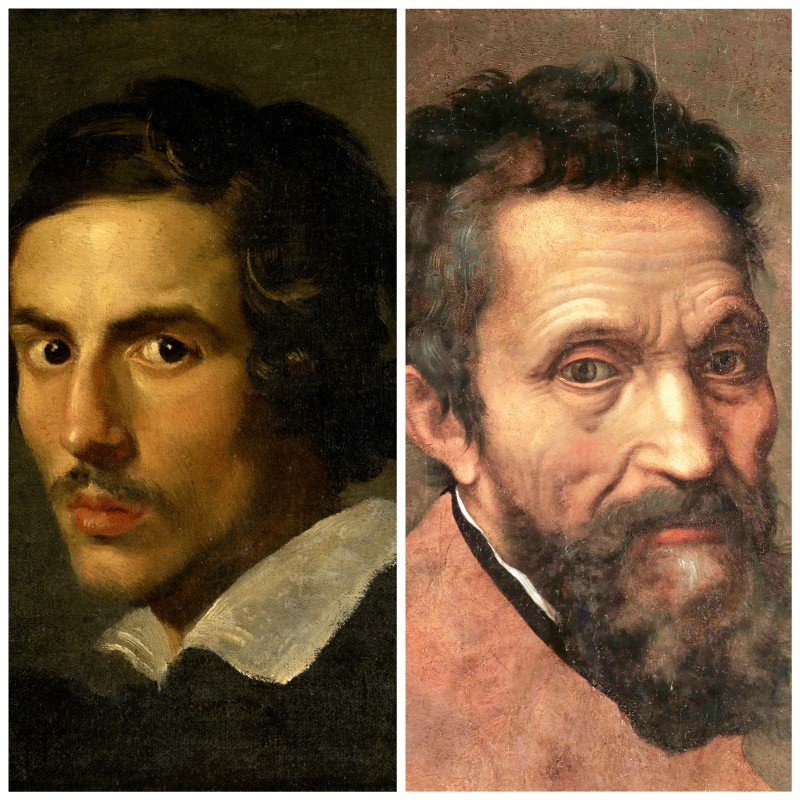

Michelangelo vs Bernini

As the last great Italian Renaissance artist, Bernini was often compared to Michelangelo from the Popes to himself. But what differentiates Bernini from Michelangelo is that he had a talent for capturing tension and drama in stone. Where Michelangelo’s David stands daydreaming, Bernini’s is frowning, biting his lower lip, bending sideways, and twisting his sling taut to let fly a stone. In another work, Bernini’s Pluto, in the act of abducting Persephone, leers as he grabs her plump waist and dimpled thigh, while Cerberus snarls at his feet. In yet another piece, Aeneas heaves Anchises on to his shoulders to save him from the sack of Troy and sets off to found Rome.

Most Complete Bernini Exhibition Ever

Now, these must-see staples have been joined by nearly 60 other Bernini works. The best museums around the world “were extremely supportive because they clearly understood that this was a unique occasion,” said Anna Coliva, the director of the gallery. “I don’t think that there will ever be such a complete exhibit of Bernini,” said Ms. Coliva.

The Villa Borghese & Gallery

“The villa itself— now a museum — built by Bernini’s first (and most ardent) patron, Cardinal Scipione Borghese ordered Bernini to fill every room to “stimulate the imagination.” (The artist crafted four monumental groups for the villa in the early 1620s — including the spectacular Pluto and Persephone and Apollo and Daphne). They demonstrate his skill at overcoming the limitations of his material, carving marble as if it were dough.”

The Exhibition Layout

Each section of the exhibition has been left to specialists in certain elements of the great artist’s career which have been separated into:

- apprenticeship with Peter

- the youth and the birth of a gender

- Bourgeois groups

- the restoration of the ancient

- busts

- the great urge

- Bernini and Louis XIV

- the sculpture craft

- and the sketches

The thoughtful placing of Bernini’s pieces within the ornately decorated Villa emphasized the best of each. Whether it is the nestling of the sleeping, newly merged, Hermaphrodite on a stone bed in an alcove, or Pluto’s strong grip on Persephone’s marble skin in the high dark ceilings, the figures fit the space they are in.

A small piece depicting the child Jupiter playing with his siblings, almost inconspicuous in the parade of some of the most famous sculptures of that entire century, was in a room painted in scenes of the story of the adolescent gods hiding from their vicious father, Saturn, in animal masks before going to Nile valley and becoming the Egyptian pantheon.

Bernini’s mark is to be seen all over Rome: the four river sculptures in Piazza Navona or in the splendour of Saint Peter’s. One still could not hope for a better space or even a better-used space in which to view Bernini than the Villa Borghese.

Highlights of the exhibition

- Pietro e Gian Lorenzo Bernini – the exhibition shows the relationship between Gian Lorenzo and his father Pietro. The curators analyze this relationship showing some Bernini’s artworks realized when he was really young and he was still working in his father workshop (es. La Capra Amaltea 1615). For a better comprehension of the association between Bernini and his father the curators displayed the 4 sculptures dedicated to the personification of the Seasons. These are a unique example of father and son working together.

- Another section of the exhibition is dedicated to the portraits that Bernini realized during his career. He made portraits of all the famous and powerful men and women of his time.

- Anima dannata, Anima beata (1619) – from the Spanish Embassy

Some more details about the Greatest Sculpted Pieces

Bust of Scipione Borghese

“When Bernini came back to sculpture, it was not so virtuosic, not so many fireworks,” says Bacchi. “He tried to capture life in a more synthesizing way—not to capture every detail but to give the impression of life.” A prime example is a bust he made of Scipione Borghese in 1632, generally considered one of the great portraits in art history. The sculptor portrayed the prelate’s fat jowls and neck, the pockets around his eyes and the quizzically raised eyebrows (below) in such a lifelike fashion that one comes away with a palpable sense of what it would have been like to be in the prelate’s presence. His head turned slightly to the side, his lips apart—is he about to share some titillating gossip?

Bust of Costanza

Even more extraordinary is the bust that Bernini completed in 1638 of Costanza Bonarelli, the wife of one of the sculptor’s assistants and also Bernini’s lover. When he discovered she was also having an affair with his younger brother, Bernini—known for an explosive temper—reacted violently, attacking his brother and sending a servant to slash Costanza’s face with a razor. What ultimately happened remains unclear, but Bernini was fined 3,000 scudi (a huge sum at a time when a sizable house in Rome could be rented for 50 scudi a year). The scandal caused Urban VIII to intervene and more or less command Bernini to settle down and marry, which he soon did, at age 40, in May of 1639. His wife, Caterina Tezio, the daughter of a prominent lawyer, would bear him 11 children, 9 of whom survived. Now ultra-respectable, he attended daily Mass for the last 40 years of his life.

Bernini’s bust of Costanza is a work with few precedents. For one thing, women were not usually sculpted in marble unless they were nobility or the statues were for their tombs. And in those sculptures, they were typically portrayed in elaborate hairdos and rich dresses—not depicted informally, as Bernini had Costanza, clad in a skimpy chemise with her hair unstyled. “He takes out all the ornaments that were important to the 17th-century portrait and focuses on the person,” says Bacchi. “You see a little of her breast, to think she is breathing, the crease of her neck so that she seems to be moving.” The portrait engages the viewer so intensely, Bacchi adds, “because it is just her expression, there is nothing to distract you.” With her mouth slightly open and her head turned, Costanza is radiantly alive. In another way, too, the bust is exceptional. Marble was expensive. Bernini’s portrait of Costanza is thought to be the first uncommissioned bust in art history made by the sculptor for his own enjoyment.

Would you like to visit the Borghese Gallery?

Discover our Borghese Gallery Guided Tour!