If the mad, bad, and dangerous-t0-know emperor Nero is famous for one thing it’s fiddling while Rome burned. The image of him performing with glee as the imperial capital burned around him has entered our lexicon. Serving as a metaphor for gross incompetence and inversion of priorities in the midst of a crisis.

The event in question was the Great Fire of Rome in 64 AD. Starting in the shops around the Circus Maximus, the fire raged for 9 days, destroying two thirds of the imperial capital. It was by no means the only fire to devastate the sprawling city. Rome’s wooden architecture and its population’s close confinement sparked numerous incendiaries that tore through the capital. But the Great Fire is notorious for one reason – many believed the emperor had started it.

We have three ancient sources for Nero’s involvement in the Great Fire: Suetonius, Tacitus, and Cassius Dio.

What the ancient authors say

Our first author, Suetonius, was an imperial courtier, who wrote his biographies of the first twelve emperors in the 110s and 120s – around 50 years after Nero’s reign.

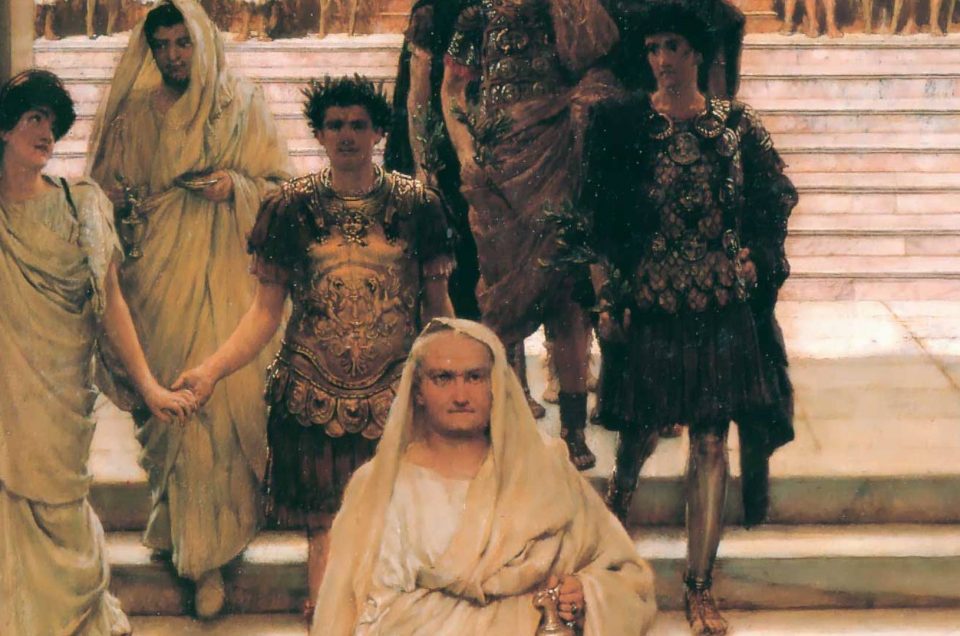

Suetonius’ largely sensationalist account describes how, as if upset by the ugliness of Rome’s architecture and its narrow, winding streets, Nero ordered the city to be set ablaze. Watching from the Tower of Maecenas (today the Torre delle Milizie overlooking the Roman Forum) and dressed up, as he often was, in stage costume, Nero warbled his way through “The Fall of Troy”.

A popular musical throwback to another fire-consumed ancient city.

Our second source, Tacitus, is less sure about Nero’s involvement.

The greatest of Rome’s historians expresses doubt as to whether Nero arranged for the fire. Some suggested he did, Tacitus muses, others put it down to divine providence. Tacitus does, however, tell us that Nero was away from Rome in the coastal town of Antium when the conflagration broke out. And that he only returned to the capital when it threatened the palace he had built between the Tower of Maecenas and the Palatine Hill.

Tacitus further credits Nero with helping out Rome’s traumatised citizenry, many of whom were said to have committed suicide upon realising they had lost everything to the flames. While some wandered Rome’s streets either fanning the flames or looting, Tacitus tells us that Nero did his best to help those most afflicted. Throwing open his private gardens to house the homeless and reducing the corn-price to help the poor.

Tacitus does tell us of a rumour that went around about Nero singing “the Fall of Troy”. But he is adamant that it was just that – a rumour.

Our third source, Cassius Dio, is of comparatively little use. Writing around 150 years after the Great Fire of Rome, he seems to have based his history on Suetonius’s biography, as he reports Nero’s complicity in the fire as concrete fact. But if the disagreement among our three sources isn’t enough to debunk one of history’s most pervasive myths, there’s one final detail: the fiddle wasn’t invented until around the eleventh century.

So even if Nero did indeed accompany himself to “the Fall of Troy”, it would have had to be with the cithara!

So where does the story that Nero burned Rome down come from?

In most likelihood, the accusation that Nero burned down vast swathes of the imperial capital was made retrospectively, by the emperors political enemies and imperial successors. The image of Nero fiddling while Rome burned and revelling in the destruction is just too farfetched to fathom.

It renders Nero a caricature of his worst characteristics. The all-singing, all-dancing performer who’s more interested in matters of the stage and being accepted as an artist than in traditional Roman values of militarism and modesty.

It’s hard to describe just how shocking it would have been to see a Roman emperor playing the fiddle or performing on stage. But imagine Queen Elizabeth II pole dancing and you get something of the idea!

Nero’s behaviour in the wake of the disaster certainly didn’t help to fan the rumour’s flames. The emperor used the land cleared by the conflagration as the site for his Domus Aurea (Golden Palace) – an almost indescribably luxurious palace spanning much of the Oppian Hill. Only a fraction of the Domus Aurea remains – though you can visit it on an experience which brings this remarkable palace to life with Virtual Reality. More often visited is the structure which Nero’s Flavian successors built on the site of his Golden Palace: the Flavian Amphitheater, which we now know as the Colosseum.

Written by Alexander Meddings